Farmers in north central Texas were almost finished planting oats in late February when the body of Sarah Forsyth would itself be sown.

Temperatures during late February 1891 reached eighty degrees or more in Jack County, where 54-year old widow Sarah lived with her married daughter Ellen Lee. Wheat crop looked promising, rainfall was not wanting, and farmers would soon turn their attention to planting corn and cotton. In mere days, the Lee family would prepare for Sarah’s own burial.

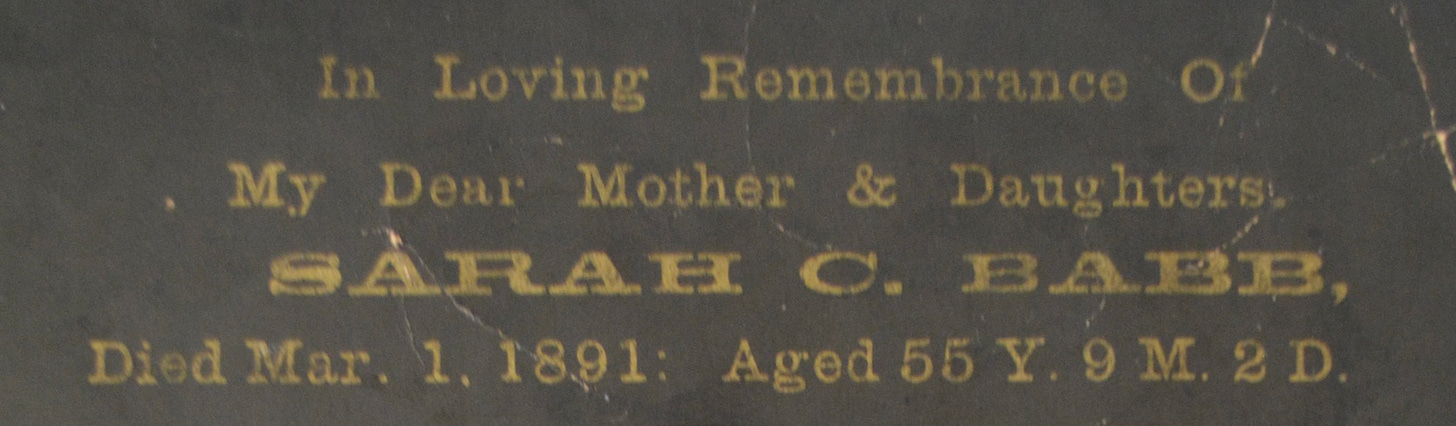

She had experienced frequent heartache, and probably aged beyond her years. Tennessee native Sarah Caroline Babb was born in 1836 as the third of eleven siblings, yet, when she was a young teenager, three of them died within two weeks, and a fourth would die a year later. They were ages 16, nine, five, and one. Perhaps to no great surprise given profound grief, the parents James and Matilda Babb soon uprooted their family to stake their future elsewhere.

They settled among the piney woods of northeast Texas for three years, completing legal requirements to own 320 acres. There she caught the eye and courtship of George Hass. He was in his mid-twenties and she was 19 when they married. Their future seemed favorable. He was the son of a large landowner, and five years into their marriage, George was an overseer1 whose real and personal property exceeded his peers. They were young parents of healthy children, Ellen and Tommy. The home was happy and hopeful.

But the Civil War disrupted their happy home. George was off to enlist in the Confederate Army in February 1862 for a one-year term of service. He wrote to Sarah from Mississippi on June 10th: “I had a very hard spell of sickness while I was gone. I stayed three weeks in Yazoo County [Mississippi] with a man by the name of Berry . . . I was as well treated as I could have been anywhere but I would had rather been at home.” In a separate letter (of unknown date), he refers to rampant sickness in his camp as not even one-third of men were able for duty, and everyone was dismounted for sixty days. “I think I will get well,” he opined. “Sarah, I would to be with you and my sweet babes to knight [sic] but kind providence does prevent but the best of friends.”

When George penned the words — and Sarah read them — did they consider the possibility that he would not get well, and that divine providence would indeed prevent him for ever returning to her? On June 28th, 1862 his sickness proved fatal. Sarah was a 26-year old widow with two young children. She probably turned to two other widows for what help they could provide — her mother and mother-in-law. But she probably realized that neither could offer the primary support of another husband, so a year later she re-married (see here for previous post on her life as Sarah Forsyth).

I can’t imagine the sorrow that Sarah must have felt when learning of the death of her husband George Hass. His letters addressed her as “dear wife,” which, while perhaps seeming ‘impersonal’, I take in context as rather affectionate. He implored her more than once to write at first opportunity, to inform him of her welfare. “I have not heard from you since I left home,” he wrote. My impression from such brief evidence of the letters is of a caring husband.

Since he had left home, he reflected on what may have been her last spoken words to him. “I think of what you said to me [often] for as soon as I reached the army I thought . . . serious on the matter.” Unfortunately, he didn’t specify, but Sarah certainly conveyed thought-provoking words that suggest youthful wisdom, or trust in God (given that the reference to divine providence immediately preceded).

That and other remembrances may have been on Sarah’s mind during her last breaths. She had kept the letters from her husband George Hass to the very end. Her daughter Ellen was almost certainly at bedside. Seven grandchildren observed what was perhaps their first experience with death, while their newborn brother was nursing or sleeping. Death had followed near throughout life and felled many close to her.

Unfortunately, no obituary existed or is extant. I have no evidence of last words. I assume she died in the faith by which she lived and was known — she was regarded a “Sister” by her circle of fellow Baptists (as indicated in her son Tommy’s obituary twelve years earlier).

The Lee family had to cross narrow Lynn Creek to inter Sarah in the cemetery of the same name.

I was last there only a couple of weeks ago, when I stopped on the way back from attending a funeral in Oklahoma. I thought of Sarah as crossing the ‘river’ and wonder if Ellen, missing her mother, thought of a popular hymn of the time “Shall We Meet” (Beyond the River):

Shall we meet beyond the river,

When the surges cease to roll?

Where, in all the bright forever,

Sorrow ne’er shall press the soul?

As Sarah’s place in life was with fellow Christians, so too in her final resting place. Her body was buried next to that of Ellen’s sister-in-law Syrenia White, of whom it was written after she died that “from time of her profession of religion until her death, she was always near the Savior’s feet.”

That testimony is how I will consider the life of Sarah Forsyth, and strive to both follow, and someday meet, her.

An overseer was a manager of slaves. George’s widowed mother Margaret Hass was a slaveowner in 1860. Ten years earlier she and husband Henry apparently did not own slaves.